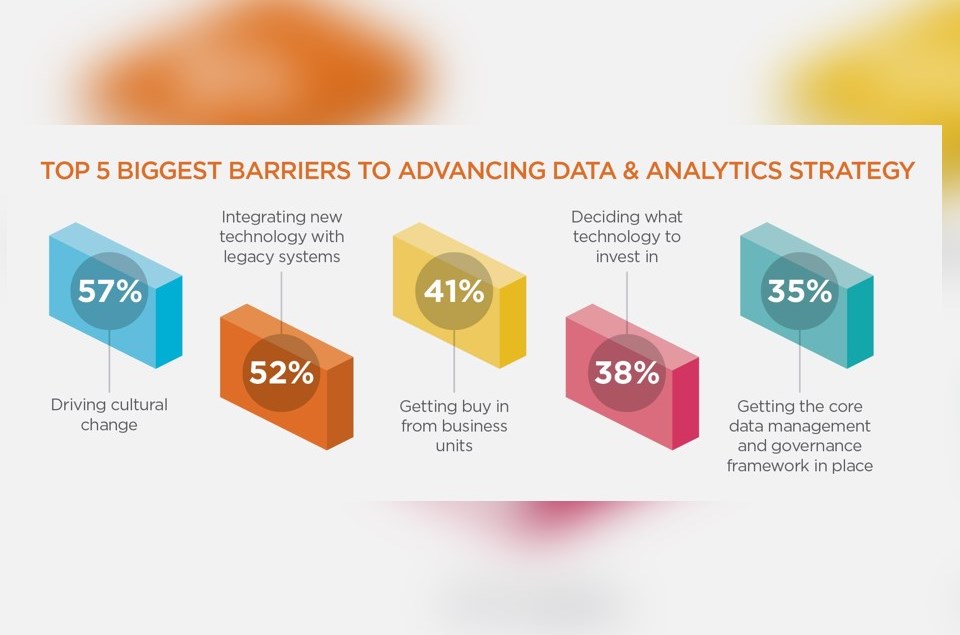

You can very successfully use network theory to analyse complexity in business. It can be fun, and easy to visualize. I personally understood why businesses can become more complex, yet more successful, analysing the evolution the network of the most successful European brands of the past 25 years –the Magnum Ice Cream. Networks theory today is extremely advanced, and lots of tools are available (see my pictures of the “Magnum Network”).

The Complexity of the Magnum Ice Cream

Italians love gelato. On hot summer afternoons, cities fill up with families strolling around, each member with a gelato in hand. I have always been part of this collective passion: when I was a teenager, my friends and I preferred to meet outside gelaterias and indulge in huge ice cream cones, rather than get drunk in bars.

In a country where the gelato is sold soon after preparation, and where teenagers prefer it to alcoholic beverages, you may wonder how packaged ice creams can possibly sell at all. But they do, and account for 30 percent of the Italian ice cream market thanks to heavy marketing and widespread distribution. Of the 30 percent, half is in the hands of Anglo-Dutch multinational Unilever, under the brand Algida.

For decades, Algida’s strongest seller was the Cornetto, an imitation of the artisanal ice cream cone, which was launched in 1959, the same year Fellini produced La Dolce Vita. Thirty years later, the country was miles away from the economic boom described by Fellini, but the Cornetto hung around and was joined by a considerable number of competitors.

The 1980s were a time of consumerist excess, with brands offering cherry, amaretto, chocolate and biscuit all in the same ice cream. It was in this environment that Unilever, in 1989, launched Magnum, the simplest ice cream bar ever –vanilla with a chocolate coating.

As an apocryphal quotation of Albert Einstein goes, “things should be as simple as possible, but not simpler”. The Magnum was simple, but not straightforward. Most ice creams had vanilla filling, but only few of them had good quality vanilla, and not one that was covered by thick, good, real chocolate. To produce good quality coating, Unilever asked Belgian Callebaut to develop a chocolate that could go down to -40 degrees without breaking, something did not exist before.

The Magnum stood out from the crowd because it was simple, yet sophisticated. According to Unilever, it was already in 1992 “Europe’s most popular chocolate ice cream bar”.

Simplicity, though, did not last for long with the Magnum. With time, the Magnum evolved from the original ice cream to an ecosystem of elaborated ice creams: Almond, Mint, Caramel and Nuts, Yogurt; bigger and smaller Magnums; even Magnums without sticks. The original Magnum, in this new fauna of Magnum Ice Creams, was renamed Magnum Classic.

Magnum’s Syndrome?

When this process of differentiation started, and the promise of simplicity was broken, I got upset. When Unilever came out with Moments, small ice creams stuffed with caramel and hazelnut, I decided the company had reached the limit, and prophesied Magnum’s fall from greatness to dust.

In conversations, whenever dealing with something unnecessarily complex, I would refer to what I called the Magnum Syndrome: “Things start nice and simple, but with time they accumulate complexity. This is when they lose their strength, like in the Magnum’s case: it is not the delicacy it used to be,there’s too much noise around.”

I could find plenty that had fallen victim to the Magnum Syndrome. World’s economy, science, politics, societies in general, Europe in particular. When Cherry Guevara was launched, together with other terrible Magnum flavours like the John Lemon, the Wood Choc, and the Jami Hendrix, I considered them the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The Magnum ecosystem will collapse soon, I was thinking while biting into my Classic. And global capitalism will surely follow.

Taming Complexity

I might have thought that science had become too complex, but I was still convinced that physics is an extremely successful tool with which to tame complexity.

Examples of physics successfully taming complexity abound. Take statistical mechanics. During 19th century, physicists studied the statistical properties of the motion of molecules in a gas and discovered that despite their seeming randomness, properties like temperature, pressure, and even the obscure concept of entropy were all explainable in terms of probability: the behaviour of billions of molecules could be described by just a few variables linked to each other.

Key to the success was creating ideal systems, like perfect gas or But how can one possibly find an ideal system with which to describe the behaviour of the stock market, human societies or the marketing strategy of Unilever?

The Network Revolution

With perfect timing, a new branch of physics was officially born together with the fauna of Magnum ice creams: network theory.

Network theory was the illegitimate child of the World Wide Web. With the Web, it finally became possible to obtain data with which to study how networks evolve. Physicists and mathematicians threw themselves into data analysis and modelling, and with new results on social topics too: networks of people exchanging email messages, web sites referring to each other, blog feeds, all produced an abundance of digital data. Results were so original that stern journals like the Physical Review begun to publish articles on social networks –a social topic, for the first time ever.

With network theory, physicists were entering the arena, and facing the complexity of the “real world” – just like biologist, economists, sociologists, and anthropologists had been doing for a while.

The power of networks is that everything can be reduced to a network and studied, even the Magnum ecosystem. As soon as we can connect two ice creams because they have in common a particular ingredient, like caramel or dark chocolate, or are part of the same offer, like the “Seven Deadly Sins”, we have a network.

For instance, the first Magnum Classic leads to the first four Magnum variations (Double Caramel, Dark, Double Chocolate, and Almond) that followed it a few years later while the Double Caramel leads to Taste (in the Five Senses) and Sloth (in the Seven Sins), which are similar ice creams that were subsequently launched.

In this way, we can draw a graphical representation of the increase in complexity of the Magnum system over time. From the simple “star” at the beginning of the 1990s, with one central ice cream and four peripheral ones…

(the size of circles is proportional to the influence)

…to the intricate network arrived at post 2000:

If we traced the evolution of the Web over the same period, we would get similar figures. We would see complexity emerge from the first 50+ webpages published by Berners-Lee in 19901 to the billion pages in 2000.

The Magnum Strategy: Complexity is Good

In complex, organised, networks, “the whole is more than the sum of its parts”, writes Herbert Simon in “The Architecture of Complexity” (1956). This “more”, this emergent property of the system –the network–, is what makes different elements get together in a network and cooperate.

Simon was right. I, on the other hand, had been completely missing the big picture when criticising complexity.

What if we thought of the Magnum Ice Creams as an organism? Being sold under the same brand, Magnums form a collaborating community: each Magnum tell us something about the other Magnums –something good – with all Magnums starting with the most excellent of reputations, based on the original Classic’s. A customer will expect, and find, good quality ingredients in any Magnum because she knows that the original Magnum’s strength was good quality vanilla, and thick Belgian chocolate. In this sense the Classic has a link with all other Magnums collaborating with them in a virtuous circle: the Classic’s reputation gets stronger as it recommends other high quality ice creams, which in turn, being actually decent, recommend the original Classic. This potential circle can exist for Magnums other than the classic. Now under the area of influence of the Caramel are the “Caramel and Nuts” and “Sloth” Magnums, which Unilever introduced after its success.

With its fast growing reputation, Unilever would continue to introduce new Magnums at a fast pace, making the Magnum empire more complex, but also more powerful. Thanks to this strategy –complexity with high quality and strong connections– the Magnum became in 2000 the largest single ice cream brand in Europe.

This success was not possible if all twenty-plus Magnums were sold by different companies, with different brands. We would see a situation similar to the one before the Magnum arrived: many over-complicated ice creams, where it is difficult to make a choice. The stronger the connection between the elements of a system, the bigger the possible success. No connections between the elements, no success.

Simon shows that Magnum’s evolution towards complexity was not just a potential syndrome, but a powerful strategy –the Magnum Strategy:

Start simple. Learn from the environment. Grow complex maximising internal collaboration

Author:

Mario Alemi, Partner, elegans.io

A few references:

- Maljers, F (1992) “Inside Unilever: The Evolving Transnational Company”, Harvard Business Review, September 1992

- Berners-Lee, T., Fischetti, M., & Foreword By-Dertouzos, M. L. (2000). Weaving the Web: The original design and ultimate destiny of the World Wide Web by its inventor. HarperInformation.

- Dorogovtsev, S, Mendes, J (2003) “Evolution of Networks”

- Clarke, C. (2012). “The science of ice cream”. Royal Society of Chemistry.